Frictionless WCF service consumption in Silverlight - Part 3: Benefits of transparent asynchrony in respect to unit testing

Introduction

In a previous article, I've shown how transparent handling of asynchronous WCF calls and use of Coroutines can greatly simplify your Silverlight's application code. Now, it's time to show how both "transparent asynchrony" and Coroutines can greatly simplify unit testing.

Prerequisites

Acquaintance with first and especially second part of this series. In this article, I'll be using both the approach and sample application from the second article, so you need firm understanding of that. You also need basic understanding of unit testing and mocking frameworks (presumably NUnit, MS Silverlight Unit Test Framework and Rhino.Mocks). If you're familiar with MS Silverlight Unit Test Framework, know how to use it and are aware of the issues which comes along, you might be interested to read this article to see how the proposed approach fixes them, though in a very unusual way.

Background

"When writing automated (unit) tests for concurrent code, you have to cope with a system that executes asynchronously with respect to the test"

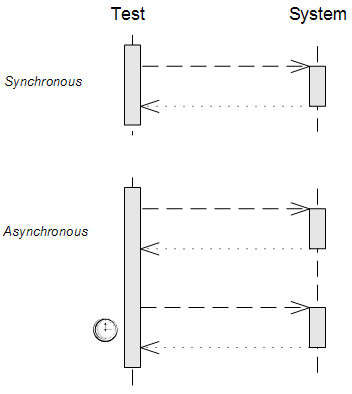

In his talk on "Test-Driven Development of Asynchronous Systems" Nat Pryce has nicely drawn the differences between automated (unit) testing of synchronous versus asynchronous code, and has summed up major problems inherent to automated testing of asynchronous code.

Synchronous test:

Control returns to test after "system under test" completes. Errors are detected immediately.

Asynchronous test:

Control returns to test while "system under test" continues. Errors are swallowed by the "system under test". Failure is detected by the system not entering an expected state or sending an expected notification within some timeout.

An asynchronous test must synchronize with the "system under test", or problems occur:

- Flickering Tests: tests usually pass but fail occasionally, for no discernible reason, at random, usually embarrassing, times. As the test suite gets larger, more runs contain test failures. Eventually it becomes almost impossible to get a successful test run.

- False Positives: the tests pass, but the system doesn't really work.

- Slow Tests: the tests are full of sleep statements to let the system catch up. One or two sub-second sleeps in one test is not noticed, but when you have thousands of tests every second adds up to hours of delay.

- Messy Tests (code): scattering ad-hoc sleeps and timeouts throughout the tests makes it difficult to understand the test: what the test is testing is obscured by how it is testing it.

Let's take a look at how the above problems are addressed in current approaches to unit testing of logic in a view model which handles asynchronous WCF calls and what the approach that I've developed in previous article brings to the table.

Current state of things

Tooling

First of all, I'd like to point out that none of the present mainstream testing frameworks (like MSTest, NUnit, xUnit etc) have built-in support for asynchronous tests. In 2008 Microsoft has made their internal Silverlight unit testing framework, which supports asynchronous tests, available for all developers. Silverlight Unit Test Framework which is now ships along with Silverlight Toolkit has introduced a number of special constructs to help developers writing an asynchronous tests. At present time Silverlight Unit Test Framework (SUTF) is the only testing framework which let you write asynchronous tests for Silverlight applications.

Let's take a look at how unit testing (with the help of SUTF) of a view models which handles asynchronous WCF calls is currently approached across Silverlight development community.

Testing against service proxies

Forget for a moment about the approaches I've outlined in first and second part of this series. Let's do it usual way. We have a WCF service and we've generated a service proxy via VS "Add Service Reference" dialog. This is the view model code we'll end up with:

/// TaskManagementViewModel.cs

public class TaskManagementViewModel : ViewModelBase

{

Task selected;

public TaskManagementViewModel()

{

Tasks = new ObservableCollection<Task>();

}

public ObservableCollection<Task> Tasks

{

get; private set;

}

public Task Selected

{

get { return selected; }

set

{

selected = value;

NotifyOfPropertyChange(() => Selected);

}

}

public void Activate()

{

var service = new TaskServiceClient();

service.GetAllCompleted += (o, args) =>

{

if (args.Error != null)

return;

foreach (Task each in args.Result)

{

Tasks.Add(each);

}

Selected = Tasks[0];

};

service.GetAllAsync();

}

...

}

To write an asynchronous test with SUTF you need to derive from base SilverlightTest class, as well as mark your method with an Asynchronous attribute. By deriving from the SilverlightTest class you get access to several EnqueueXXX methods. These methods let you "queue" up code blocks (delegates) with the code you want to execute asynchronous.

To test that current tasks are queried from a service on a first activation and a first one is selected by default, a corresponding SUTF test may look like the one below:

[TestClass]

public class TaskManagementViewModelFixture : SilverlightTest

{

[TestMethod]

[Asynchronous]

public void When_first_activated()

{

// arrange

var model = new TaskManagementViewModel();

// this will be used as a wait handle for call completion

bool eventRaised = false;

model.PropertyChanged += (o, args) =>

{

if (args.PropertyName == "Selected")

eventRaised = true;

};

// will not execute next queued code block until true

EnqueueConditional(() => eventRaised);

// act

model.Activate();

// assert (queue some assertions)

EnqueueCallback(() =>

{

Assert.AreEquals(2, model.Tasks.Count);

Assert.AreSame(model.Tasks[0], model.Selected);

});

// queue test completion code block (tell SUTF we're done)

EnqueueTestComplete();

}

}

Let's leave aside the "beauty" of the view model code and discuss the test itself. While, with time you will get accustomed to all those special constructs, and will be able to filter them out as a unnecessary noise, IMHO it's difficult to understand an intent of a test, when it is polluted with all those special constructs.

Loss of test expressiveness is not the only problem. You still need to explicitly synchronize with the "system under test". Silverlight unit testing framework need to know when the asynchronous call is actually finished (so it knows when it is ok to execute rest of the queued code blocks).

In the sample test above, the value change of specific property ("Selected") is used as the wait handle, signaling SUTF that asynchronous call has been completed (so it may proceed further). This idiomatic (and frequently used) approach is fragile and clutters test code. Imagine if you logic has changed and you don't need to select the first task on activation anymore. If you expect the unit test above to break on the line

Assert.AreSame(model.Tasks[0], model.Selected)

then you'll be surprised to discover that, instead of failing assertion on this line, the test will rather hang completely. You will need to manually debug it to find out a cause. The problem here, is that an indirectly related indication is used as the criterion of call completion. The change of property value is rather one of the outcomes of a call completion and not a genuine fact. Of course, you can resort to using more robust call completion indicators, like using ManualResetEvent (or similar signaling objects). But then you will be polluting your production code with things unrelated to its primary functionality, with things which are there, only for the sake of testing.

But the biggest problem, is that by testing against real service proxy, we're testing against real thing! This gives us all sort of headaches like:

- Flickering Tests - changes in test data will break the tests despite the behavior is still ok

- Slow Tests – almost any service out there have some kind of persistence and IO operations adds lot of latency, plus the execution time of server logic itself, plus the latency of real network call, plus …

- Messy Tests – in addition to special constructs and synchronization overhead, there is also an overhead related to complex test setups, when you're testing against real things. Here you will need to correctly setup both server and client side parts

All of the problems mentioned by Nat Pryce are still relevant to this kind of automated testing. Also, it's difficult to stimulate exceptional scenarios and to test alternative code branches like error handling logic, because you will need to somehow setup an exceptional scenario on a server-side.

Taking in account all of the above mentioned problems and obstacles, developers are having with unit testing of asynchronous calls of WCF services, when trying to write unit tests against real service proxies, it's no surprise that people are more inclined to skip unit testing such logic than to get all of the burden.

So, what could be done to remedy this situation?

Mocking asynchronous interfaces

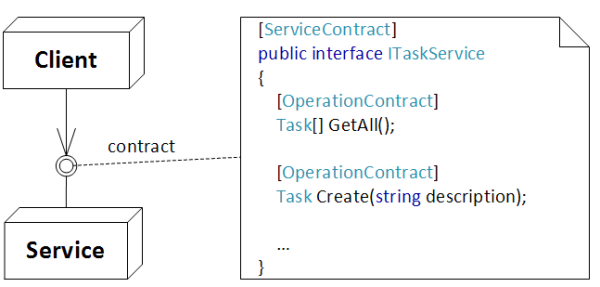

Testing against real service is against "test one thing at a time" principle. Moreover, you have probably already tested a server-side services in isolation, don't you? And by taking in account that server-side already provides an established protocol, in terms of a service contract, we have all excuses to simply "mock" an interaction with it (by mocking an interface calls).

But mocking generated service proxy is impossible, all generated methods are sealed. You can try to wrap it manually instead, but the overhead is enormous and will greatly reduce unit tests ROI.

Instead we can try to work against an asynchronous interface (which is generated along with service proxy code) and mock asynchronous calls with a help of mocking framework. This is the second major, but less popular option, used across Silverlight developers community.

While generated service proxy class utilizes event-based asynchronous pattern (EAP), the generated asynchronous interface uses asynchronous programming model pattern (APM). This changes the code in the following way:

/// TaskManagementViewModel.cs

public class TaskManagementViewModel : ViewModelBase

{

...

ITaskService service;

public TaskManagementViewModel(ITaskService service)

{

this.service = service;

...

}

...

public void Activate()

{

service.BeginGetAll(ar =>

{

try

{

var all = service.EndGetAll(ar);

foreach (Task each in all)

{

Tasks.Add(each);

}

Selected = Tasks[0];

}

catch (FaultException exc)

{

// ... some exception handling code ...

}

}, null);

}

}

As you can see, this is the pretty standard APM callback-based kind of code. Notice how the interface is injected via the constructor. This allows to pass an instance of generated service proxy class (which implements this interface) in run-time, and also to pass a mock object in a test harness.

/// TaskManagementView.xaml.cs

public partial class TaskManagementView

{

public TaskManagementView()

{

InitializeComponent();

}

private void UserControl_Loaded(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

// here we pass an instance of generated service proxy class

var viewModel = new TaskManagementViewModel(new TaskServiceClient());

DataContext = viewModel;

viewModel.Activate();

}

}

The unit test which uses mocking may look like the one below (here I'm using Rhino.Mocks as my mocking framework of choice):

/// TaskManagementViewModelFixture.cs

[TestMethod]

public void When_first_activated()

{

// arrange

var tasks = new ObservableCollection<Task>

{

CreateTask("Task1"),

CreateTask("Task2")

};

var mock = MockRepository.GenerateMock<ITaskService>();

var asyncResult = MockRepository.GenerateMock<IAsyncResult>();

// need to setup expectations for both APM methods

mock.Expect(service => service.BeginGetAll(null, null))

.IgnoreArguments().Return(asyncResult);

mock.Expect(service => service.EndGetAll(asyncResult))

.Return(tasks);

// pass mock to view model

var model = new TaskManagementViewModel(mock);

// act

model.Activate();

// we need this to actually complete the call

Callback(mock, service => service.BeginGetAll(null, null))(asyncResult);

// assert

Assert.AreEqual(tasks.Count, model.Tasks.Count);

Assert.AreSame(model.Tasks[0], model.Selected);

}

static AsyncCallback Callback<TService>(TService mock, Action<TService> method)

{

var arguments = mock.GetArgumentsForCallsMadeOn(method);

return (AsyncCallback)arguments[0][0];

}

static Task CreateTask(string description)

{

return new Task {Id = Guid.NewGuid(), Description = description};

}

While "mocking" approach is much more reliable and easier to use, than testing against real service, a test code still looks clumsy. The problem here is not with the approach itself, but rather with the fact, that we're trying to mock an asynchronous interface, and this is where all the inconvenience comes from.

Mocking APM based code incurs significant overhead and obscures clarity of the test. The essence of a test is just "between the lines". Compare it with regular mocking of pure synchronous interface:

// arrange

var mock = MockRepository.GenerateMock<ITaskService>();

var model = new TaskManagementViewModel(mock);

var tasks = new[] { ... };

mock.Expect(service => service.GetAll()).Return(tasks);

// act

model.Activate();

// assert

Assert.AreEqual(tasks.Count, model.Tasks.Count);

Assert.AreSame(model.Tasks[0], model.Selected);

The difference in clarity is huge:

- You don't need to setup any additional expectations – for APM you need to setup expectations for both methods from APM method pair

- You don't need to constantly filter out Begin\End prefix noise

- You can clearly see what is passed to the method - there no 2 special additional arguments which are required for every BeginXXX method and which are completely non-relevant in a test

- It is easy to see what is returned from a mocked method – with APM mocking, a method call is split into a two methods: BeginXXX method always returns IAsyncResult and an actual value is returned from EndXXX method

- No additional, tech-only rubbish, like dealing with IAsyncResult, which further obscures an intent of a test

- You don't need any special call completion constructs, like invoking AsyncCallback delegate

However, there is also a great positive outcome from mocking an asynchronous service interface – mocking approach fixes all major problems inherent to asynchronous tests. How? Well, it turns out that by mocking an asynchronous calls in a unit test, a "system under test", start being synchronous, and thus a unit test!

In normal environment, the system is still run asynchronously, it's just when it runs in a test harness, it runs in synchronous mode. This duality of execution is a powerful concept to exploit. Let's see how we can apply it to the approach implemented in the previous article.

Frictionless unit testing

Transparent asynchrony and dual mode execution

As you remember from the previous article, we've managed to remove the friction, coming from the obligatory (platform) requirement to use an asynchronous interaction with WCF services in Silverlight, and we did it by enabling developer to work completely against a synchronous interface, while auto generating an asynchronous APM-based interface and handling an asynchronous calls in a transparent fashion.

Let's recall some code from the previous article (how the view model code looks like):

public class TaskManagementViewModel : ViewModelBases

{

const string address = "http://localhost:2210/Services/TaskService.svc";

ServiceCallBuilder<ITaskService> build;

...

public TaskManagementViewModel()

{

build = new ServiceCallBuilder<ITaskService>(address);

...

}

...

public IEnumerable<IAction> Activate()

{

var action = build.Query(service => service.GetAll());

yield return action;

foreach (Task each in action.Result)

{

Tasks.Add(each);

}

Selected = Tasks[0];

}

...

Here, we're using a normal synchronous interface. However, there is a substantial difference in invocation: instead of calling its methods directly, the invocation is specified via Lambda Expression. This allows underlying infrastructure to inspect the expression, recognize method call signature and arguments passed to it, and then project the invocation onto an asynchronous twin interface, while transparently handling APM callbacks.

The fact that Lambda Expression is used to specify an invocation of a method, makes it simple to implement an ability to mock an invocation for unit testing purposes, while preserving an asynchronous behavior of view model's code in run-time. So, let's do it!

First of all, we need to give a developer the ability to pass an instance of mock (in a test harness). This is rather straightforward:

public class TaskManagementViewModel : ViewModelBases

{

const string address = "http://localhost:2210/Services/TaskService.svc";

ServiceCallBuilder<ITaskService> build;

...

public TaskManagementViewModel(ITaskService service)

{

build = new ServiceCallBuilder<ITaskService>(service, address);

...

}

...

Then we need to provide a way to set the execution mode. Depending on whether it's set to synchronous or asynchronous - compile lambda expression and execute it on a passed mock, or transparently project it onto an asynchronous interface respectively. Here, we can kill two birds with one stone - the underlying infrastructure can figure out the execution mode automatically, depending on whether an instance of an interface (ie mock) was passed or not:

public class TaskManagementViewModel : ViewModelBases

{

public TaskManagementViewModel()

: this(null)

{}

public TaskManagementViewModel(ITaskService service)

{

build = new ServiceCallBuilder<ITaskService>(service, address);

...

}

So, the default constructor will be used in a production code, while the overload will be used to inject a mock instance in a test harness.

For infrastructure part, everything is also really straightforward:

public abstract class ServiceCall<TService> : IAction where TService: class

{

readonly ServiceChannelFactory<TService> factory;

readonly TService instance;

readonly MethodCallExpression call;

object channel;

protected ServiceCall(ServiceChannelFactory<TService> factory,

TService instance, MethodCallExpression call)

{

this.factory = factory;

this.instance = instance;

this.call = call;

}

public override void Execute()

{

if (instance != null)

{

ExecuteSynchronously();

return;

}

ExecuteAsynchronously();

}

void ExecuteSynchronously()

{

try

{

object result = DirectCall();

HandleResult(result);

}

catch (Exception exc)

{

Exception = exc;

}

SignalCompleted();

}

object DirectCall()

{

object[] parameters = call.Arguments.Select(Value).ToArray();

return call.Method.Invoke(instance, parameters);

}

static object Value(Expression arg)

{

return Expression.Lambda(arg).Compile().DynamicInvoke();

}

void ExecuteAsynchronously()

{

channel = factory.CreateChannel();

object[] parameters = BuildParameters();

MethodInfo beginMethod = GetBeginMethod();

beginMethod.Invoke(channel, parameters);

}

...

Now you can write a unit test like the one below:

[TestClass]

public class TaskManagementViewModelFixture : SilverlightTest

{

[TestMethod]

public void When_first_activated()

{

// arrange

var mock = MockRepository.GenerateMock<ITaskService>();

var model = new TaskManagementViewModel(mock);

var tasks = new[] { CreateTask("Task1"), CreateTask("Task2") };

mock.Expect(service => service.GetAll()).Return(tasks);

// act

Execute(model.Activate());

// assert

Assert.AreEqual(tasks.Length, model.Tasks.Count);

Assert.AreSame(model.Tasks[0], model.Selected);

}

}

The only nuisance here is that, as we're relying on iterator-based Coroutines, in order to trigger an execution of method's code, we need to actually traverse an iterator. This is done by the simple helper method:

void Execute(IEnumerable<IAction> routine)

{

foreach (var action in routine)

{

action.Execute();

}

}

That's it. Simple and elegant.

Résumé

As you can see, we've approached the problem from a completely opposite side - instead of exhausting developers by forcing them to code against an "evil" asynchronous interfaces and adding unnecessary friction to development, transparent asynchrony gives you the ability to code completely against normal synchronous interfaces – both in production and test code.

It seems like we removed all friction, but there is still one big thing left to improve …

Bonus is Frictionless Tooling

Microsoft Silverlight Unit Testing Framework is quite powerful thing, but with power, it also comes with the set of limitations:

- You can only run tests within a browser process

- You can't run tests with alternative test runners, like TestDriven.NET, ReSharper etc

- You can only get/see test run results via the bundled GUI, and this throws Continuous Integration out of the window (*can be fixed with StatLight project)

- You can't get code coverage tools working, because of all above mentioned limitations

Well, for me, this list is already a showstopper. I found it hard to justify the cost of using SUTF as my unit testing framework of choice. As I've already got rid of asynchrony in unit tests (and thus don't need any special testing framework support for asynchronous tests anymore), and my view models are simple POCOs (see footnote), I immediately started looking for other options.

FOOTNOTE: If you really understand the MVVM pattern, then you know that view models are just about state and behavior. So they're better off implemented as simple POCO objects. A view model should not depend on UI concerns (like DependencyProperties, main thread affinity and so on), otherwise, it will be difficult (or even impossible) to keep it testable.

It's a common misconception that Silverlight code could only be executed within a context of a browser (via Silverlight plugin). In fact, long ago (back in 2008) Jamie Cansdale researched that Visual Studio designer hosts Silverlight for use in the designer window and rather than host a separate instance of the CoreCLR, the designer simply loads the Silverlight assemblies into the host runtime - which is the .NET CLR! This means that Silverlight assemblies could be loaded into the .NET CLR, as if they're normal CLR code! This is due to CoreCLR compatibility with .NET CLR.

Jamie did manage to tweak the 'nunit.framework' assembly so it's compatible with Silverlight projects and that did make possible to run, debug and even do code coverage on Silverlight unit tests! All existing .NET CLR tools which support NUnit (like TeamCity, ReSharper, TestDriven.NET, NCover etc) will be able to recognize, load and run NUnit tests contained in Silverlight assembly.

As this was a long time ago, the version of NUnit framework recompiled by Jamie got ancient, but thanks to Wesley McClure for his efforts, we now have Silverlight compatible version of NUnit 2.5.1. You can go grab it from his blog. Then you may simply create new "Silverlight Class Library" project, reference Wesley's assembly and start writing unit tests. It's that simple!

FOOTNOTE: There is one catch, in order for your tests to execute successfully, you also need to ensure that all referenced Silverlight assemblies (except 'mscorlib') are set to 'Copy Local: True'. And make sure that your view models are in fact POCOs, so you don't need browser context in order to exercise them. In particular this made me change my dispatching implementation from using System.Deployment.Dispatcher, which is only available within a context of a browser, to the more ubiquitous and robust SynchronizationContext (see attached example).

If you're a long-time fan of MSTest, you can actually use its Silverlight version instead of recompiled NUnit assembly to write unit tests, as long as you stick to the rules outlined in footnote above.

Conclusion

To keep this article short, in the next (and the last) article in this series, I'll show you the whole new array of tricks and techniques, which could be used to unit test an asynchronous code, using Coroutines and transparent asynchrony. We will look at, how easy is to test "repeatable actions" and "bouncing transitions" by utilizing such a simple technique as "history tracing". Also we'll explore how the advanced scenarios, which I've discussed in the previous article, such as Fork/Join and Asynchronous Polling could be unit tested as well. I'll also touch on subtle bugs that could be introduced due to environment fluidity and external scope bindings, and how unit tests could be written to cover such cases.

Download attached sample application to see how view model unit tests could be written. The latest version of the source code could be found here. There also a lot of other goodies you can find, like using Coroutines with blocking wait and using transparent asynchrony in non-Silverlight environments. Additional material related to the topic I'll be posting on my blog.

发表评论

I noticed that it's hard to find your website in google, i found it on 22th spot, you should get some quality backlinks to rank it in google and increase traffic. I had the same problem with my blog, your should search in google for - insane google ranking boost - it helped me a lot